January Book Blog: NPCs, Situations, Events and a GLoG class and Call of Cthulhu 7th career from Tim Harper's Underground Asia

Introduction and Short Review

TL;DR: How revolutionaries (first Anarchist, then Marxist, then nationalist) began to undermine imperialism in Asia, 1900s-30s. Fantastic read if you're good at remembering lots of names.

Underground Asia is a marvellous work of the kind Allen Lane/Penguin History seems to manage on the regular: pop-history enough to be a snappy and enjoyable read, well-cited and meticulous enough that you wouldn't feel uncomfortable referencing it yourself. All those who talk about journalists writing better books than historians, take note; all those who sneer at non-academic publishing houses, likewise.

The book itself is a history of motion: mobile people, mostly a sometimes-bewildering array of early 20th century Asian revolutionaries criss-crossing the world on missions of liberation, and the times they move forward with them. The majority of its narrative follows a dozen or so major protagonists and scores, perhaps a hundred+, of minor ones from the 1900s through the 1930s, with a few roots and branches poking out in either chronal direction. Harper argues that

These mobile Asians abroad were among the first people to experience world history. They experienced it not as an idea but by coming and going, as workers and also as colonial subjects, in a way that brought capitalism and imperialism closer together in their worldview. Liminal spaces – locations of sudden displacement and new solidarities little understood by metropolitan elites, such as port city slums and the mining and plantation frontiers of the tropical colonies – became the foci of world-historical change.

How that world-historical change was predominantly conceived - read 'what ideologies were driving it' is another core throughline of Underground Asia. To grossly oversimplify, the dominant revolutionary movement early on, is anarchism - specifically, the sort of propaganda-of-the-deed solitary and murderous anarchism which has darkened the broader reputation of the ideology ever since. Early anarchist action inspires a nearly supernatural dread in the Imperial powers: 'Its effect lay as much in the anticipation as in the bomb or the bullet itself: the dread that they could puncture time and order at any moment and without forewarning.' But dread provokes repression, co-ordinated and generally effective. Then, with the imperial powers divided and weakened by the Great War, the Russian Revolution shatters the previous political sphere. Within years, Marxists are the driving force behind resistance to empire, fighting with strikes and espionage as much as with weapons. A wave of attempted revolutions in the late 1920s largely fails, and the torch begins to pass somewhat in the book's closing third to liberal nationalist movements of the sort who the anarchists were rejecting in the first place, now inspired to a new pitch of militancy that will eventually - outside of Harper's scope - usher in a new Asia.[1]

(Yes, that new Asia will be heavily influenced by Marxism, but the immediate revolutions will be predominantly nationalist ones which will violently oppose Marxist efforts at co-option, c.f. Madiun.)

Against all of this, the imperial powers struggle and/or refuse to evolve. They're immensely powerful (less so year-on-year, especially after the Great War, but always an overwhelmingly dangerous opponent) and yet slightly, darkly, comical. They spend years or even decades chasing rumour and misinformation, catch the wrong people or let the right ones slip through their grasp, and when they do catch a genuine revolutionary they monologue about justice and morality during the show-trials; all this whilst indulging in nostalgic, orientalizing imaginings of the places they rule which seem to amuse even visitors from the imperial core. Nobody has an easy time - the unpredictability of violence as a method forms another theme, from the faulty detonator up to the revolution failed due to a misread map. ‘If an act by one person or a few could set great revolutionary events in motion, equally the right man at the border post, or in the harbour master’s office, could stop them in their tracks.' But the imperial powers come across as especially fumbling. Harper adopts the historian-standard neutral affect, but it's very clear (or so it seems to me) where his sympathies lie throughout from where the textual camera lingers, whether it makes frustrating tragedy or subtle slapstick of a given silly decision. The balance is well-struck, to my mind.

The other thing worth highlighting is just how ordinary the revolutionaries are. Mao Zedong is gossiping about his colleagues' love lives in a cafe. M.N. Roy is taking some time off to enjoy a nice hotel on Comintern money whilst his marriage disintegrates. (A lot of it's psychosexual). Tan Malaka is worrying about repaying the cost of his tuition. You're in the present tense, with them, as people who don't know they're going to change the world yet. There are only one or two travellers in the global political sphere the book covers who feel like they already know where they're going to, and even then one suspects it's because they're sneaky enough that we're seeing them through imperial intelligence's rather paranoid eyes. The old TTRPG trope of players accidentally getting involved in a revolution which they suddenly become deeply committed to, or taking a day off from fighting an evil lord at a critical moment to pursue a random personal sidequest? Possibly not TTRPG tropes. I think that's both interesting from a game perspective and quite encouraging, given the world in general.

Post Overview

This post is going to go through a few examples of the things the book does best: its descriptions of people and places, and the dynamic, chaotic, madly-spiralling events it chronicles, picking out those which could easily and interestingly be slotted into your TTRPG games. The best examples, of course, are long and too complex to quote; they will require you to read the book itself.

Most of the examples I've given refer to the real-world context; you could use them as-is in a game set in early-20th-century Asia, or swap out nations, time periods etc. for ones suitable to your own game. I'm mostly going to assume you're able to do that and keep my editorializing to a minimum.

I'll close out the piece with an experimental little GLoG class I've made, and a Call of Cthulhu career and Mythos Tome should you want to play as an Asian revolutionary wanderer of the period. I picked both because they're simple; GLoG because it's happy to play with some narrative-manipulation tools whilst still being basically interested in chaotic, weird, gritty & violent action; and CoC because the time period fits well. I'd have loved to make more of the reality-puncturing anarchism quote above and make some Mage: the Ascension content too, but I couldn't think of anything that wouldn't be covered by the game as it stands. (Maybe I'll come up with something after reading Erica LaGalisse's Occult Features of Anarchism.) Suffice to say there's a lot of Mage-y stuff in there!

You might also find content useful for basically any game featuring one or more empires, ideally maritime empires, ideally at an early-20th-c tech level or some simulacrum thereof. [2]

NPCs

Example 1: 'Fat Babu'

'Rash Behari also imparted his knowledge of firearms and bombs; in one demonstration … a detonator in a biscuit tin went off, badly damaging the third finger on his left hand. By this he could be identified, but few who met him knew his true name: instead he was “Satish Chandler” or “Fat Babu”. [This was the name the British knew and hunted him by.] He posed as a sanyasi – a religious mendicant – a shopkeeper, a scavenger. It was said that, in the guise of the shopkeeper, he “borrowed” a colleague’s wife as his own. It was also said that he evaded police cordons dressed as a woman; that he made a fool of one Indian officer by reading his palm; and that he duped a British policeman by travelling in a first-class railway carriage disguised as an Englishman. When the last ruse became known, it was said the officer “could not stir out of his bungalow for a week for shame”. The legend of this Lord of Misrule travelled vast distances, a harbinger of a greater struggle to come.’

There's an overlong story later in the book where Behari (in disguise in Japan) meets revolutionary poet and politician Bhagwan Singh at a dinner party, who eventually identifies him by his scar, leading to much hilarity between the two. They go on to share a car whilst fleeing an attempted arrest.

Example 2: 'Goodman'

'There were any number of more opportunistic adventurers [in China]. In 1919, the British followed a man called Goodman, one of many similar individuals, “giving conflicting accounts of himself and behaving in a most suspicious manner”:

At the British Consulate he claimed to be an Egyptian, and said he wished to return to Egypt. As the only papers he could produce were written apparently in Arabic on dirty leaves torn from a notebook, and bearing neither seal not [[sic]] stamp, he was refused assistance until he could obtain proper proof. It was later discovered that he came from Tientsin [Tianjin], where he had represented himself as an American Presbyterian Missionary to the USA Consul, by whom he was rejected as an imposter.

In Shanghai he booked rooms in three different hotels, and booked a passage to Hong Kong, saying he was a banker. He also applied to the USA Consul for a passport to Hong Kong, saying he was born in New York, but has lost his papers.

He is about 5 feet 10 inches in height, heavily built, very dark, looks like an Assyrian or Hindoo and wears black clothing.

I think both of the above examples illustrate that a setting aiming for this tone basically has to have red herrings. I know that's not conventional wisdom, but you need players to be genuinely unsure whether the person they're investigating/chatting with has anything going on or whether they're just a bit odd, even/especially if they're looking for allies rather than hunting revolutionaries like the British are here. That, and you need the possibility that if there is anything going on they'll never find out.

Example 3: Maximillien De Colbert

‘Canton was a magnet for adventurers and speculators. On 19 October 1922, there were six bomb attacks in the city and suburbs … A forty-eight year-old doctor working at the Republican Hospital, Maximillian de Colbert, was arrested. A “stout active man with a Hohenzollern moustache,” he had acted as chief surgeon to Sun Yat-Sen’s northern campaign. The military authorities, who initially apprehended him and claimed to have been watching him for some time, uncovered bomb cases, secret notes and photographs of government officials targeted for assassination. De Colbert was said to have had three secret meetings with Sun Yat-Sen while he was exiled from the city, and trained protégé assassins by throwing rubber balls. The doctor’s son, “fearing for his father”, led the military to 100 pounds of dynamite hidden under some rubbish in his laboratory. The doctor’s interpreter was also arrested. De Colbert claimed the empty shells were souvenirs from Flanders and that the recovered bombs had been found by his children playing in the streets. He possessed chemical compounds as he was setting up a modern sanatorium. There was much confusion over his origins and, hence, his claims to extraterritorial legal privileges. He was born in Aachen, and supposedly brought up in Belgium; he qualified as a medical doctor in Germany and had worked in the United States in rural Wisconsin in 1917-19. He spoke German, French, English, and Russian, none of them, it was said, very well. His story, as he told it, was that he had organized a relief mission in Canada for Armenia after the armistice, travelling by camel to Kars. But his funds were lost in a dubious foreign exchange deal and he and his family had to make their way to Samara and Bokhara. He maintained that he had fled the Bolsheviks and ended up in Vladivostok in 1920. His wife was American, and de Colbert claimed American citizenship as well, but the US consul hesitated to intervene. At various times he said he was German and British.. When questioned, he answered: “Yes, I am an anarchist. But there are four kinds of anarchists, and I am one of the Tolstoy type, doing educational work.” … In January 1923 he was released by the district court on lack of evidence. His interpreter died in prison. There was no resolution on the questions as to whether the incidents were related or who might be behind them. The whole bizarre affaire seemed to be symptomatic of a deepening struggle between anarchists, communists and nationalists for the soul of the city.’

See my above point. Also an interesting illustration of the privileges of European anarchists as against their Asian comrades (poor interpreter). And a plot?

1d20 short NPCs

- A Muslim prince married into a Punjabi ruling family; described by Nehru as “a character out of medieval romance, a Don Quixote who had strayed into the 20th century”, but proudly pan-Asian and committed to the overthrow of the British Empire.

- A street speaker for the International Workers of the World, with half a dozen names and no clear history even to his allies; prone to disappearing to the other side of the world when things go bad.

- A foreign revolutionary leader trying to rebuild a shattered organization, 'as much a competitor as a collaborator, but ... still ... a meeting point for revolutionaries of all nations.'

- A blind Russian 'poet, anarchist and esperantist' (speaker of Esperanto, the internationalist conlang) who frequents a bohemian bakery-restaurant in Tokyo.

- A 16-year-old railway clerk and 'a minor aristocrat turned trade union propagandist' who between them have more than decupled the numbers of their local transport union since taking over its newspaper.

- A former foreign leader and war criminal repeatedly trying to escape his exile in increasingly implausible disguises, plagued by plane-crashes but determined to take his revenge and rebuild an empire worthy of Alexander the Great in central Asia.

- The head of Chinese detectives in an Anglo-American enclave, living a double-life as a gangster.

- A powerful business magnate, semi-deified by local temples as an entrepreneur and city father unjustly cheated by colonialists; those same colonialists keep selling their businesses to him to keep them from going bust.

- The '“Examiner of Questioned Documents”', who IRL examines intercepted letters 'for angularity, pen pressure, idiosyncrasies of spelling and other marks by which the expert eye might distinguish one hand from another' but might do anything that name implies!

- A Vietnamese mandarin's son in exile, showing an 'uncanny ability to move easily between the worlds of the intellectuals and the workers’ cafes' much to the frustration of the security services trying and failing to follow him.

- A woman who pleads for mercy for her murder of a state official with an enigmatic smile, claiming "bad temper"; demonized by the press as an exemplar of modern immorality.

- Ex-pirate and former military officer in a dissolved anarcho-federalist alliance now hired by police as the leader of a band of mercenary strikebreakers.

- The "Cromwell of China", a Christian-convert warlord who baptizes his highly-trained troops by firehose with the aid of a Canadian revivalist. Backed by the Soviets, sympathetically treated by the Western press, seen as rather cynical by rivals.

- A merciless warlord who will always take the time to have his mercenaries execute his own officers for failure, even as he runs down his own troops in his haste to flee danger.

- ‘The commander of the city garrison ... sent out a judge with two swordsmen to mete out summary justice to the strikers by beheading … between 19 and 23 February the General Labour Union claimed there were at least forty [of these] executions.’

- An expat community who seem to have completely missed the last 25 or so years of history. Pilloried by journalists

- A band of influential communists fleeing nationalist persecution in China by rail, drinking horrifying amounts of wine, rumourmongering and flirting with each other all the way.

- A fictional 'man of multiple aliases and magical powers, whose clandestine international organization allowed him to appear at crucial moments to challenge injsutice and reveal truth.' Tales of him strongly resemble the movements of a real revolutionary.

- A quiet, sickly outcast political philosopher sheltering under the protection of a brutal renegade battalion commander in a small village as he attempts to take command of a national revolutionary movement by mail.

- A famous Soviet emissary with a cultured middle-european affect, living in luxury abroad as he frantically sends his many go-betweens to track down the misplaced Romanov diamonds he was planning to use to fund international revolution.

Locations/Grand Situations

Example 1: Tashkent, 1920

‘In 1920, the elegant old city of Tashkent was now a major military outpost of Soviet Russia; its commissars commandeered the hotels and the best provisions. The whole region was hit by desperate food shortages. It too was a strangely cosmopolitan place. There were many Austro-Hungarian prisoners of war, who provided orchestras for the cades and restaurants. An Englishman with a troupe of performing elephants passed through on his way to Kashgar. There were also British agents at large, including in 1918 Colonel Frederick Marshman Bailey. One of the last of the Great-Gamers, his presence was no secret; the band at the most fashionable café would break off and play ‘Tipperary’ when he arrived. Towards the end of the year he was arrested, only to escape and return disguised as a prisoner-of-war. His spectral presence stoked Soviet fears of counter-revolutionary activity and triggered a violent crackdown after the so-called “January events” of 1919, an incipient coup d'état, quickly crushed by the increasingly brutal Cheka in the city. Bailey’s self-appointed[[!]] role was to set up networks of couriers and agents to monitor all these comings and goings. Tashkent was a staging post for Indian traders, military deserters and the men recruited by Abdur Rab and Acharya into an Indian Revolutionary Organization.’

Example 2: British Malaya, 1914

‘To a wealthy, industrial colony such as British Malaya, the war came swiftly. The years since 1905 had seen a boom in exports: in 1914 some 1,168,000 acres of plantation produced 37.8 per cent of the world’s rubber. … it created a pool of wealth from which could be drawn war taxes and 5,172,174 Straits dollars in donation to voluntary war funds and charities … the government and the Malay sultans subscribed to a battleship, HMS Malaya. But all this demanded a reckoning. The sultans were showered with high honours and Asian merchants demanded new recognition.

…

War with Germany deepened affinities of blood. The Germans in Malaya were themselves a diverse community of traders, physicians, hoteliers, journalists, bandleaders and missionaries. Now long-term residents such as H.C. Zacharias, a British citizen, the secretary of the Selangor Club and the man who imported the first British motor car into Kuala Lumpur, were threatened wit hinternment and the deportation of their families. Ugly rumours pursued Britons suspected of “pro-German” sympathies at every level of the colonial hierarchy, including Lady Evelyn, the wife of the governor, Arthur Young. … Sequestration exposed the sheer extent of commercial inroads by German businesses. It also led to an acute shortage of beer. Many Chinese traders oreferred dealing with Germans as they gave longer credit and “dealt with Asiatics and Eurasians as men to men”, as one local paper told it … But by mid-1915 the trade of the Sulu islands of the southern Philippines, which had been largely in German hands, had been seized by British ships and by neutrals. … The principal German trading company in Singapore, Behn Meyer & Co., lost everything in Malaya but re-registed in Batavia, under Dutch protection. There the company’s leading men, Emil and Theodore Helfferich, brothers to a minister in the Kaiser’s government, attempted to mobilize the company’s twenty—one ships, 500 sailirs abd other personnnel in anti-British intrigues. … The European war took away 20 per cent of the Malayan Civil Service’s “heaven-born”, or forty-five British officers. In total 700 European men left the federated Malay States during the war, and 200 of them would lose their lives. Those who remained were denied leave, and this took a silent toll, with men suffering from alcoholism, hallucinations and madness … There was a minor epidemic of suicides.

…

Colonial society was haunted by the spectre of weakened prestige. No fewer than twenty-one readers and translators were put to work censoring the mail. The first revelations they stumbled upon, however, were the British community’s own dark secrets. A schoolrteacher in Ipoh – the man who brought association football to Malaya – was intercepted writing, on the suggestion of someone at his club, to a former pupil in Singapore to arrange an assignation: “You know what I like, if you can arrange I’ll pay you what you want. Do you understand I wonder, jantan [cock] about fifteen?’ This was, the British Resident commented, a bit much, “even for the Ipoh Club”, and the man was permitted to resign “to avoid a grievous scandal.”

Example 3: Harbin, 1921

|

| Found here, attribution and dating not given but seems to be approximately right |

‘The eastern gateway to China was the town of Harbin, which emerged at a strategic junction where the Chinese Eastern Railway branched south to the port of Dalian on the Yellow Sea to connect in Shenyang to Tianjin and Beijing. … Effectively it was a Russian corridor 1700 miles long … It had served as a vital supply line during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5, when Harbin was a place of rest and recreation for Russian officers. In 1921, it was a company town of some 200,000 people with a unique pidgin-Russian as its lingua franca. No one heading to China could avoid it, and the flood of refugees overwhelmed the Russian administration. Existing residents – including over 9,602 young Russians born in the city – became emigres “by default”; part of the growing “flotsam of the revolution”. Harbin’s population was swelled by an influex of Chinese as it became the gateway to the mines and frontier farming of Manchuria: it was fast becoming a Chinese town. Americans came to Harbin to sell their heavy agricultural machinery and saw it as a mirror of their own “Wild West”. And so too did Japanese in greater numbers: labourers recruited from Northern Kyushu, shopkeepers and prostitutes. Most of the branch line south of Harbin was in Japanese hands, and there were periodic clashes with Chinese troops. The Chinese occupied Harbin in December 1917, but … only by June 1920 did Chinese troops finally oust Russian police and railways guards and deport 300 of them back to the Soviet Union. The issues of sovereignty in the region … culminated in mass protests in February 1922 at the “Thirty-Six Sheds”, an area of cramped and squalid settlement for Chinese railway workers: a microcosm and metaphor for China’s impoverishment and desire for change.’

1d16 one-sentence Places & Powder-Kegs

- Tiny town - one underpaid police officer, mails unmonitored, governor living in fear after a bombing in his home three years prior. As such, the primary ingress point of anarchists into an entire nation.

- Public park serving as an improptu camp of thousands of foreign radicals and draft-dodgers, with its own culture, periodicals and schools.

- An expat anarchist quarter, with its own educational facility and lodging-house, built around a soya bean factory founded by an industrious migrant.

- Requisitioned, vermin-infested hotel in Moscow, full of socialists from all over the world come to work for the Comintern; a strict hierarchy of the best-quality rooms, rigorous induction rituals when you check in, operatives are referred to by room number.

- Special train, doubles as a theatre, used to display propaganda as it passes through settlements. In good times, locals welcome it with animal sacrifices and fanfares.

- Port, full of disaffected and highly mobile wage-labourers of a religious minority, with connections all through the city and along the coast.

- Marshy delta, home to urban sprawls containing 'perhaps the greatest concetration of toiling humanity on earth' but with plenty of space in the wetlands for brutal river pirates to thrive. Dominated by a massive seaport and riverport at opposite ends.

- Drab Indian courtroom. Raised platform with chairs for a judge and three assessors; semicircular table for the counsel, and a high chair for an interpreter (judges rarely speak the local tongue) where a jury should be. Guarded by regularly-rotated Sikh policemen.

- Former provincial governor's residence split between two rival generals of the force that has captured it, one a Soviet attaché, one a Chinese nationalist. 'The air [is] tense with plots, and the intimacy of their earlier relations [is] at an end.’

- A 'floating concession' of warships and pleasure-barges, last enclave of an imperial power along a waterway. When the river is high, it still projects their authority; useless, even vulnerable, when it is low.

- Arid volcanic island 400 miles off Mexico, with one spring (at low tide), some seabirds, a small population of remarkably hardy sheep, and a reputation as a place for revolutionary ships to meet or cache messages in bottles.

- Fake embroiderers' workshop, serving as cover for a group of foreign revolutionary women to travel abroad to study without their families objecting.

- Plantation colony, born of rapid deforestation for rubber planting; a nominal model of colonial ethics, maintained only by constant manipulation of death statistics which makes even colonial clerks uneasy; plagued by quiet rebelliousness.

- Cosmopolitan tradeport full of enclaves of warring imperial powers, all trying to intrigue against each other without breaking the local law and thus creating an excuse to expel them.

- Warrenlike alleys of shikumen houses, somewhere in style between Northern English terraces and classical Chinese architecture; endlessly sublet and subdivided; full of street schools and radical printing presses.

- A city under bitterly-resented and brutal occupation by a desperate and near-collapse Communist army led by its former civil governor. Foreign warships watch over their own interests from the harbour; nationalist armies circle the periphery.

Events

Example 1: The Voyage of the Emden

‘As the battle of the Marne began far away in France, the light cruiser SMS Emden, part of the Imperial German Navy’s East Asia Squadron under Admiral Spee, was detached from the armoured cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau as they steamed across the south Pacific towards the Atlantic. It entered the waters of the neutral Netherlands Indies; then, passing through the Lombok Straits, it infiltrated the Indian Ocean and travelled up the west coast of Sumatra. The Emden announced its presence in early September by attacking Allied shipping. For over two months it jeopardized the British empire’s island coaling stations and telegraph relay stations for the “All Red” routes that were the strategic sinews which connected the Asian and Pacific colonies. In a surreal episode, the Emden was careened, coaled, provisioned and royally entertained by the coconut plantation bosses on Diego Garcia, a British-held island which had not yet heard the news of war. More ominously, the cruiser threatened the prison colony of the Andamans. Defence plans were hurriedly drawn up.

The Emden raided Madras on 23 September, hitting the oil tanks of the Burmah Oil Company, and there was public hysteria when Britain’s oldest outpost of the islands, Penang, was bombarded on 28 October. The German ship slipped in using the ruse de guerre of flying Japanese flags and displaying a dummy funnel. Its torpedoes sank the Russian cruiser Zhemchug, leaving eighty-nine Russians dead and 123 injured, and its guns destroyed the French destroyer Mousquet, killing thirty Matelots. When it was finally cornered and forced aground in the Cocos Islands in early November, survivors from the crew managed to escape by boat to Sumatra. The Emden’s phantom-like existence stoked febrile rumours … The lesson was clear: if one ship could unsettle imperial networks in Asia, what might more concerted action achieve?’

Random encounter: That one enemy warship. Also, it's wrecking all the communications networks characters might normally use to get news, rumours etc. until you do something.

Example 2: Spider-Prophet

‘There was a sensation in Province Wellesley in Malaya in December 1921 when a spider was rumoured to have spun the words “Mahatma Kand”, seemingly to signify Gandhi.. The police had to break up crowds of spectators, and there was at least one copycat incident. An Amritsar paper reported that “On banana leaves there appear the figures of Mahatma Gandhi, Mohamed Ali and Shaukat Ali,” the leaders of the Khalifat movement. The British saw in this the hand of the millionaire son of a Sikh businessman of Kedah. Three more apparitions occurred in Perak in April the following year. They were swiftly destroyed by the police, but the third in particular, on a piece of wasteland near the Sikh temple and the Tamil settlement, attracted hundreds of visitors, with tradesmen and educated clerks “solemnly riding in carriages to the scene. Carvings appeared on benches. The signs were clear to all: Gandhi was in prison and must not be forgotten.’

Couldn't find a photo for this one, alas. I think you get the picture though. There's a plot hook for amoral adventurers: destroy these prophetic images of an imprisoned folk hero that just keep popping out of natural events! Or for more heroic types - fabricate such things yourself.

Example 3: Naren in Tianjin

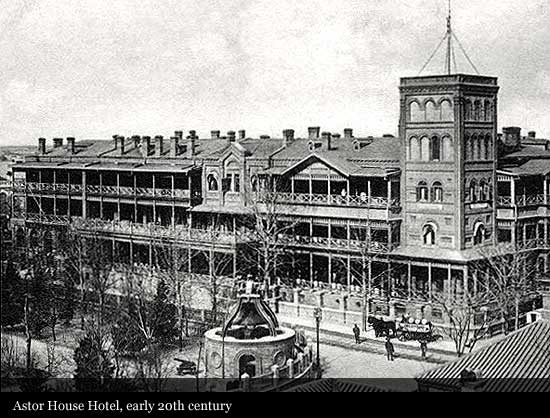

|

| Photo from https://www.historichotelsthenandnow.com/astortianjin.html |

I include this section to illustrate some of the spatial elements of safety and how they might be violated. In a city broken into different territorial zones, you can well imagine the drama that could arise by playing cat-and-mouse around them, trying to stay in safe areas whilst achieving objectives.

‘Tianjin was China’s fifth largest city … and was dominated by the British Concession, Naren looked to make contact with the large numbers of Indians: traders, labourers and some 700 policemen under British officers with Russian and Sikh sergeants.’ In the deadly game of chess that all fugitives played, Naren learned in advance thaty the railway station was just outside British extraterritorial control. However, on the platform itself he was greeted by a “typical colonial tough”.

“Good afternoon, Mr White.”

Naren ignored him and kept walking. The man fell into step beside him. “Before you go to your destination, would you mind accompanying me for a few minutes?”

Naren asked him where and why. “To the police station; I am chief of the British Police.”

Naren knew that the German concession, safe ground, was just a street in front of him. “I am very tired after the journey and would rather go straight to a good hotel. Moreover, I believe we are not in British territory.”

“That’s alright,” the policeman pulled hum up. “I know my business. Really, I may not detain you long.”

There was a car waiting, and Naren was taken to the police station. He was told he would spend the night there while the British awaited information from Japan. Dinner was ordered from the Astor hotel, the epicentre of the social life of Tianjin’s diplomatic circles.

“How did you know I was coming?” Naren finally asked.

This was met with a laugh. “Oh, the Japanese police is very efficient. Good night.”

He was under armed guard, Sikhs initially, but they were soon replaced by British troops. In the morning he was taken before the British consul-general, sitting as magistrate. Naren claimed to be a student travelling to England but impeded by the war … He said that he “was frightened and wanted to return home, but desired to see a little of the world along the way.”

This time, the hazard of legal process played Naren’s way and, to the chagrin of the policemen, he was set free. The policemen asked him where he was heading: “To a good hotel”. He checked in at the Astor, which – as the policeman reminded him – was in the British concession. But he needed a hot bath and a good meal. That afternoon, Naren took a rickshaw into central Tianjin. He sensed he was being followed. He took refuge in a store,, and when his pursuers repaired to a tea shop he slipped out the side door, down a lane to the river, and took a ferry to the German concession nearby.’

Naren would travel on, eventually reaching the Americas where he'd take on the name M.N. Roy, by which you may have heard of him.

1d20 one-sentence Happenings

- A ship passes through; many rumours swirl that it's carrying a cargo of arms for revolutionaries and their criminal allies. It should be, but in fact it missed its rendezvous and carries no arms at all. The intended recipients - German spies, Indian rebels and criminals - will be unhappy.

- A group of exiled Indian revolutionaries disguised as Persian nobility hold secret meetings in parks where they plot to kill a fraudulent English explorer and pose as him and his retinue to infiltrate India.

- The secret police harry poor families selling their religious iconography on the markets after a harsh winter. Not merely cruel: forged and stolen official documents can also be had on the bazaar, for the right price.

- A foreign nation collapses and citizens living locally lose all standing; the consulate is boarded up, legal cases collapse and assets are stripped. The desperation and scheming of the survivors turns them into archetypal femmes and hommes fatales of the zeitgeist.

- A city's black market is buoyed by an expanding drugs trade and a massive surplus of arms from a recently-ended foreign war. Entire police stations worth of officers are dismissed for corruption, whilst raids simply push gangsters across nearby borders.

- A state-approved popular press, the "Palace of Reading", sets up hundreds of stalls from classroom bookshelves and travelling salesmen to full shops, selling subtly censored material with a positive spin on empire.

- After a long, shaky alliance with trade-unionists, gangs unite with a new military dictator, and armed by imperial powers, to break a general strike: assassinating union bosses at meetings, serving as shock troops and intimidating pro-union small businesses.

- A popular work of semi-academic sexology 'cause[s] such a sensation that crowds queuing to buy it ha[ve] to be dispersed by fire hose.' Its author seeks a radical transformation of more than just societal mores...

- A 'travelling circus' passing through Romania is revealed to carry concealed arms and radios, intended for an invasion of India via Afghanistan.

- Emissaries of a revolutionary sect criss-cross Latin America and the Middle East 'on neutral ships, with ill-defined missions and unknown credentials.' Funds from Germany go missing regularly; false names are traded back and forth; everyone has an angle.

- Police officers of colonized peoples in foreign ports are dismissed, exacerbating an ongoing wave of migration and raising tensions as weapons-trained and disillusioned young men return home en masse.

- A German-Swede drops cryptic yet accurate hints to the government about the plots of the German government, insisting that all communication be via coded ads in the local paper.

- The elephant-mounted police ride to arrest a local revolutionary, who hears them coming and flees. They find only a single news cutting and an annotated map. Two days later, the fugitive is killed in a firefight after offending some villagers who inform on him.

- A young Canadian typist with diplomatic connections rushes all across Asia, leading to great consternation amongst the imperial powers. She will later claim to have been travelling for an abortion after a liason with a wealthy American, stating travel-induced miscarriage as the reason she never actually had one...

- In a mass trial for sedition, disagreements on defence strategy lead one defendant to shoot another dead with a smuggled gun and take a shot at the judge before being gunned down. Eventually, 1 acquitted, 29 convicted, 2 dead, 1 certified as insane.

- After a wave of political repression, 'Alongside their editors-at-large, newspapers now lis[t] their “editors-in-prison”.’

- It's become a trend amongst the cool young revolutionaries to get a colonial scholarship then pointedly decline. Class numbers fluctuate wildly.

- A deposed general, reduced to guerrilla war far from his homeland, is killed in a skirmish. His body is not identified for days; then, all of his old enemies become terrified that he's faked his death, assuming he's still lurking in the region for years.

- An important policy debate within a communist cell is interrupted when a case of mistaken address and a murder next door are assumed to be signs of an imminent police raid. Delegates travel two hours by train to reconvene on a boat on a scenic lake.

- An imperial prince has an increasingly despondent tour through a subject nation, greeted at every turn by Potemkin hunting trips with drugged animals, murderous anti-colonial riots, and natural disasters.

The Person of Motion, a GLoG class

A: Hidden Networks

B: Bomber

B: Advance Warning

C: Slip Between Worlds

C: Assassin

D: Untouchable

D: Movement Maker

Skills (2d6 nested):

Who Are You?

CoC 7th ed Content

Career: Revolutionary Exile

Revolutionary exiles are in an interesting position as regards the Mythos; not because their peoples have some special connection to it, though imperial-core esotericists and anthropologists (and New England horror authors...) have certainly tried to claim this, but because for them more than most the established order of things is not worth preserving. Torturous and nightmarish horror, violence and depersonalization are already a reality for those suffering under the imperial boot at home, and so some - especially of more anarchistic stripes - may have more than a little sympathy for the idea of shattering the world's fundamental laws.

Credit Rating: 8-80

Suggested Contacts: Political sympathizers and fellow-travellers, pro bono lawyers, crooked police officers, ordinary oceangoing sailors, organized criminal groups, trade unionists, regular travellers

Skills: Any two interpersonal skills (Charm, Fast Talk, Intimidate, Persuade), Disguise, Firearms (Handgun), Language (Other), Listen, Stealth, any one other skill as personal or era specialty.

Tome: Ketrocohan ing Wektu/Puncture in Time

None of the original publishing circle have been identified, apart from the eight arrested at the printers' in 1926. Six of these were members of the PKI, one of the religious nationalist Sarekat Islam (SI) party, and one of no known political identity. None of them were politically prominent, though one had been a trade union organizer of some standing until 1922. Three had been educated in the Netherlands, and the rest had strong records in local schools, where two were now teachers. Of these, one of the SI members was killed during capture, the other two non-PKI members were imprisoned for six years each, two of the PKI members placed in internment camps indefinitely, two more sentenced to exile in the Boven-Digoel camp in Western New Guinea on unrelated charges of possession of illegal arms, and the last committed to the Krankzinnigengesticht Magelang mental institute.

Sanity Loss: 1 if one issue is read; 1D6 if at least eight issues are read; 2D4 if the complete surviving set, including the 'lost' final issues, is assembled and read.

Cthulhu Mythos: +1/+6 percentiles

The end!

[1] I read Harper as being most sympathetic to the anarchists in this cycle; as somebody who'd tend to self-describe as anarcho-communist if pressed to a one-word label, I can only bring myself to extend them so much grace. A lot of them are basically violent lone-wolf killers with a thin veil of political ideals unbacked by a theory of change, which would be understandable if a lot of them weren't also rich well-educated folks, and perhaps justifiable if their hasty actions didn't get large numbers of people around them - including more thoughtful anarchist activists but also apolitical members of the public - imprisoned or killed through misplaced bombs and government reprisals. I'm not in love with the Marxists or liberal nationalists here either, but I didn't expect to be. The anarchists disappoint me.

[2] As I say that I find myself wanting to start another Traveller campaign...

Comments

Post a Comment